Hence, as the COP30 meetings in Belém, Brazil have just finished, I thought it would be fitting the first monthly market report (Monthly Market Report or the Report) synthesises the outcomes of the meetings based on my discussions with contacts that were on the ground and in the negotiations as well as the views of respected global journals, universities and news outlets.

Overview

The 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30), the international negotiations between countries around curbing climate change just concluded in Belém, Brazil. I would argue the meetings delivered some incremental advances on finance, forests and non‑state action, but fell short on fossil fuels, near‑term implementation and protection for vulnerable countries.

The meetings left a widening gap between climate ambition and the current backward looking real‑economy. Key economic trends that are powerful generators of future facing jobs and sustainable GDP growth led by technology were not advanced at the desired level. For sophisticated business and policy audiences, the summit underscored both the durability of the Paris framework and the growing fragility of geopolitical consensus, especially after the United States’ effective withdrawal from their traditional high‑ambition leadership position. The loss of American leadership further empowered other countries with strong vested interests in the incumbent system to obstruct key objectives such as phasing out fossil fuels and their substitution with tech led solutions such as renewable energy, industrial batteries and green hydrogen solutions among many others.

Political Context and Overall Verdict

COP30 was widely billed as the “COP of implementation” and an opportunity for Brazil to showcase climate leadership from the Amazon. However, the final outcome was judged by many major media and expert institutions as weak on core mitigation. The final decision text did not include an explicit roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, a result described as a victory for producer countries such as Saudi Arabia and Russia and a setback for Brazil’s presidency, which had called for such a plan.

I agree with the analyses that many converged on that the COP30 marginally “inched the world forward” institutionally, while failing to match the accelerating pace of physical climate impacts and clean‑energy deployment in markets. As already noted, the absence or reduced engagement of the United States as a force pressing the Gulf producers and other countries on ambition exposed deep geopolitical fractures in the UN climate process.

Mitigation: Fossil Fuels and Energy Transition

On mitigation, the core failure was the inability to secure a negotiated fossil‑fuel transition roadmap, despite a coalition of more than 80 countries and over 150 major businesses and civil‑society organisations backing language to move away from oil, gas and coal. Producer states and some emerging‑economy exporters opposed binding or time‑bound phase‑out language, leading to a watered‑down text that avoided directly naming fossil fuels even as the main driver of warming.

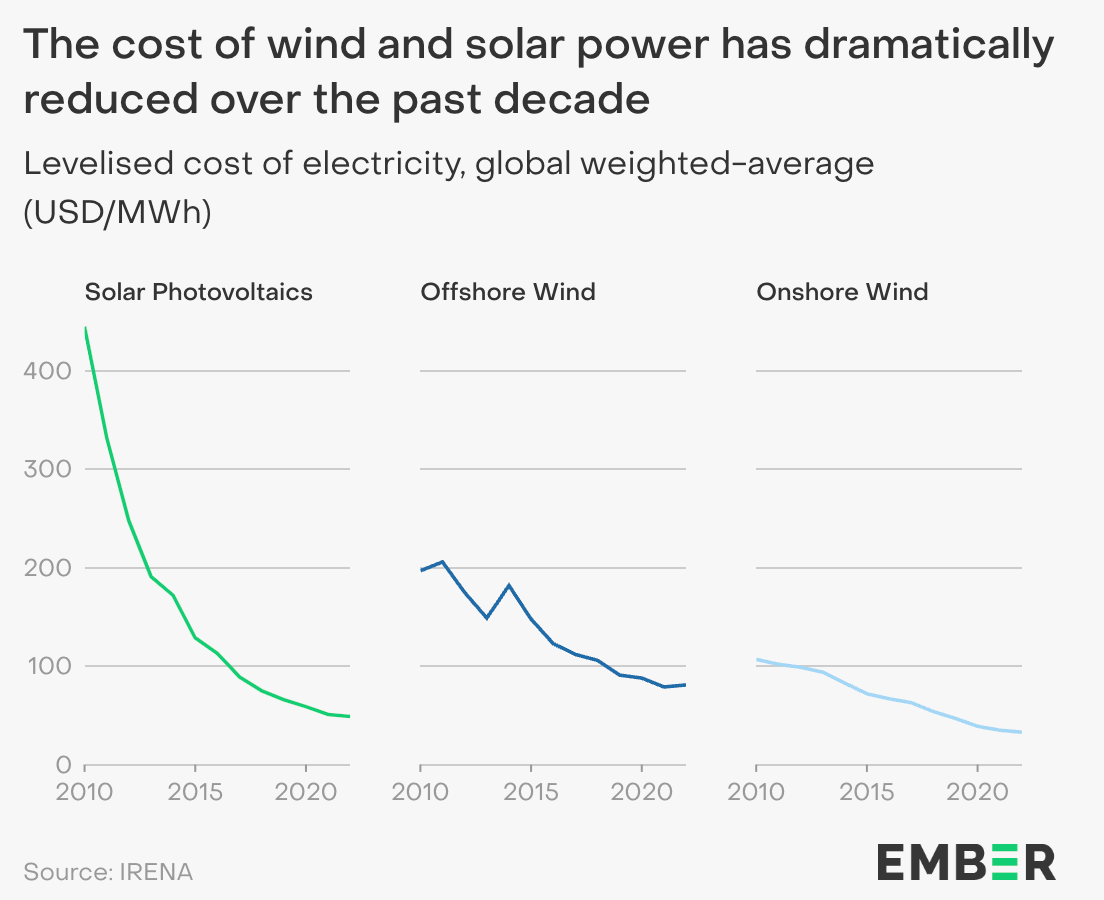

For markets and corporates, this outcome prolongs policy uncertainty in sectors such as upstream oil and gas, heavy industry and shipping, even though capital expenditure and deployment trends are already tilting towards electrification and renewables in many key economies. Many people on the ground as well as observers understand the “real economy” is moving faster than national negotiating stances, particularly in large emerging markets where renewables and electric vehicles are scaling well ahead of formal nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Forests, Land Use and the Amazon

Forests and land use were one of the clearest areas of progress, reflecting the Amazon forest setting and Brazil’s strategic priorities. Reuters reported that Brazil announced the demarcation of 10 new Indigenous territories covering almost 1,000 square miles, a significant governance step for safeguarding forest carbon sinks and Indigenous rights. At the same time, expert assessments stressed that COP30 still did not produce a negotiated, time‑bound global roadmap to end deforestation, leaving implementation of earlier pledges off track for the 2030 halt‑and‑reverse goal.

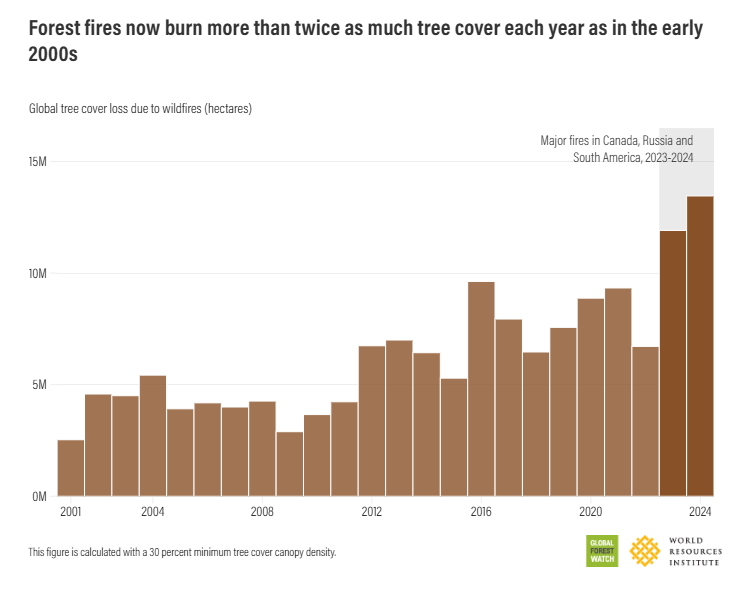

The summit nonetheless consolidated new initiatives, including a large‑scale Tropical Forest Forever Fund aiming to mobilise roughly 125 billion dollars through loans and investments to incentivise conservation of tropical forests, alongside Brazilian‑led road‑mapping efforts on deforestation outside the formal UN text. Brazil also helped launch a voluntary “Call to Action” on integrated fire management and wildfire resilience, intended to combine science, policy and Indigenous knowledge in response to record‑breaking fire‑driven forest loss. However, these voluntary initiatives often do not get converted into meaningful action and results and forest fires burn more than twice as many tree cover than in the early 2000s (see below chart).

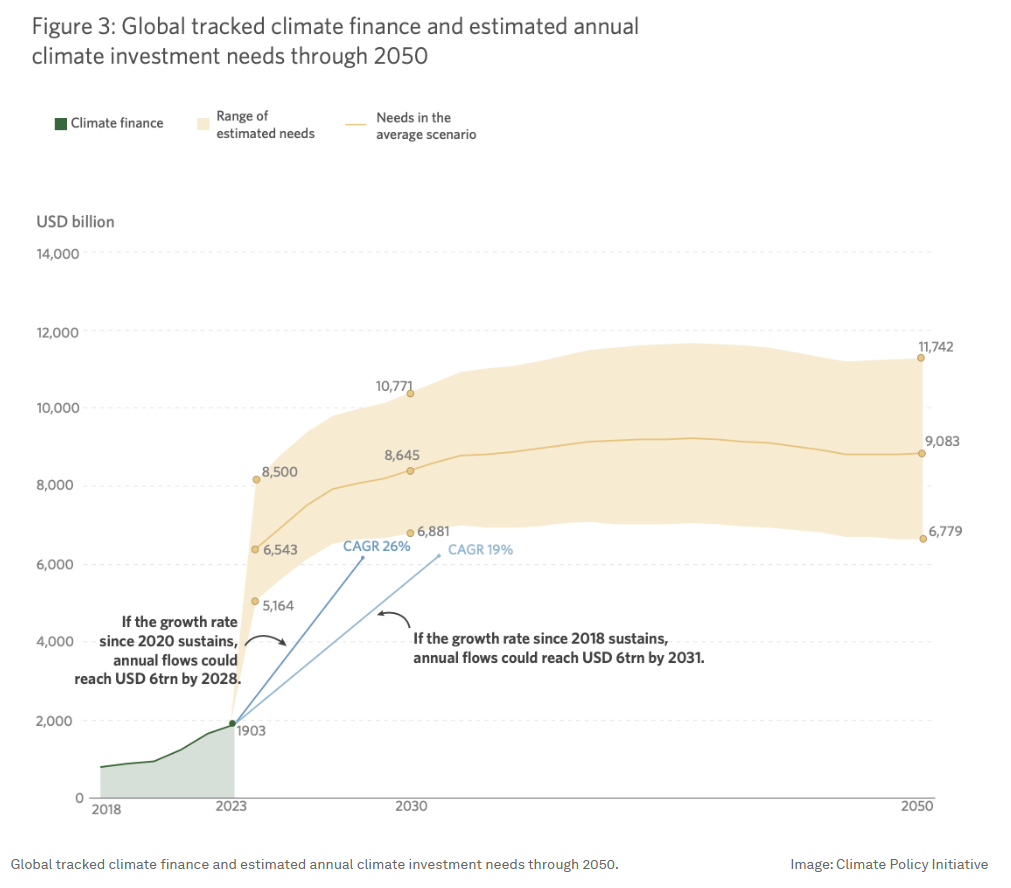

Climate Finance and the Mutirão Decision

On climate finance, COP30 adopted the Mutirão decision, which sets a trajectory towards 1.3 trillion dollars per year in climate finance for developing countries by 2035 and calls for at least a tripling of adaptation finance. This represented a political signal that finance must move from billions to trillions, reinforced by a new two‑year work programme and high‑level process to operationalise the post‑2025 finance goal. This is a step in the right direction and many countries in ASEAN could benefit from this increase in funding.

Yet many (including myself) analysing COP30’s outcomes point to persistent gaps between needs, promises and actual flows, particularly for vulnerable economies. Estimates presented by loss‑and‑damage experts suggested annual needs of at least 724 billion dollars for loss‑and‑damage finance alone, while the newly established loss‑and‑damage fund remained capitalised at well under one billion dollars, a scale many described as “deeply concerning” and I would say deeply disappointing relative to escalating climate impacts.

Scale of Finance Gaps

The Mutirão climate‑finance trajectory for developing countries (1.3 trillion dollars per year by 2035), estimated annual loss‑and‑damage needs for emerging markets (around 724 billion dollars) and the current capitalisation of the Loss‑And‑Damage Fund established at COP 27 (about 0.4 billion dollars). Even with the political step‑up implied by the Mutirão decision, the gap between actual needs and disbursable resources for loss and damage remains orders of magnitude wide, with direct implications for sovereign risk, infrastructure resilience and supply‑chain stability in vulnerable regions.

Loss and Damage: Architecture vs Delivery

Institutionally, COP30 did strengthen the loss‑and‑damage architecture by clarifying the roles of the Warsaw International Mechanism, the Santiago Network and the new Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD). The Mutirão decision linked “urgent and enhanced action and support” on loss and damage to broader finance ramp‑up and tasked the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM) with a stronger focus on delivery, including non‑economic losses and compound risks.

However, both city networks and specialist consortia highlighted there is still no credible commitment to scale up actual loss‑and‑damage finance commensurate with needs, and that channels for local and sub‑national access remain weak or indirect. For fragile states and frontline communities, this means that, despite more elaborate governance structures, near‑term protection against climate shocks remains underfunded and overly dependent on fragmented project‑based interventions.

Business, Cities and Non‑State Actors

From a business and sub‑national perspective, COP30 was more positive, with a large Action Agenda consolidating more than 480 initiatives involving thousands of companies, investors, mayors and civil‑society organisations. Analyses by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and others note corporate and city‑level engagement – particularly from US firms – was higher than at COP29, with many business coalitions explicitly calling for a predictable fossil‑fuel transition framework to guide investment and risk management.

For cities and regions, COP30 marked what some described as a “breakthrough”, with clearer recognition of urban climate action in implementation pathways and a stronger mandate for locally led approaches in adaptation and loss‑and‑damage support, even if formal access to national and global funds remains limited. sophisticated To AGFM, these signals reinforce the trend that credible net‑zero strategies increasingly depend on alignment with city‑level planning, transport electrification, building decarbonisation and resilient infrastructure agendas.

Social Justice, Indigenous Leadership and Protests

Symbolically, holding the summit in Belém heightened expectations around indigenous leadership and environmental justice, and there were tangible recognitions alongside visible contestation. Many media outlets reported that Indigenous leaders played a more prominent role in official sessions and side events, while Brazil’s announcement of new demarcated lands and support for integrated fire management responded directly to their advocacy.

At the same time, Indigenous protesters blocked entrances and organised demonstrations against both fossil‑fuel expansion and the perceived failures of the COP process to address structural drivers of deforestation and climate vulnerability. Critical voices argued that without explicit fossil‑fuel phase‑out commitments and enforceable protections for territories, the increased visibility of Indigenous leaders’ risks becoming more symbolic than transformative.

Implications for Business and Policy

For globally exposed businesses and policymakers, COP30 sends a dual message: the multilateral climate architecture is still moving – on finance frameworks, forest initiatives and non‑state alignment – but not at the speed or clarity required for orderly decarbonisation and resilience planning. The continued absence of a negotiated fossil‑fuel phase‑out roadmap, combined with under‑funded loss‑and‑damage mechanisms, leaves transition and physical risks under‑priced in many portfolios and heightens the importance of scenario‑based, jurisdiction‑specific analysis rather than reliance on COP outcomes alone.

At the same time, advances on forest protection, wildfire resilience, city‑level engagement and large‑scale private‑sector mobilisation underscore that opportunities for climate‑aligned investment are deepening, particularly in emerging‑market infrastructure, nature‑based solutions and adaptation‑linked finance. For sophisticated actors, the lesson from COP30 is not to wait for perfect consensus texts, but to treat the summit’s mixed record as a floor – and to anchor strategies in the faster‑moving dynamics of technology, capital markets and sub‑national governance that the Belém conference only partially managed to capture. We at AGFM will remain at the forefront of identifying green and sustainable technological companies and investments that will drive investment returns as well as propelling the world towards a high growth, sustainable future.

I wish everyone a happy and prosperous holiday season, and I look forward to providing you with my New Year review in my next Report.

Redefining the Future of Sustainable Investment & Family Dynamics

Asia Green Fund Management is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as Capital Markets Services (CMS) provider based in Singapore, dedicated to advancing Asia’s sustainable future through high-integrity green investments. Our services span Family Office Advisory, Private Equity & Venture Capital and Private Credit, with a focus on green technologies and infrastructure. We invest in scalable solutions that drive environmental and social impact across the region.

Asia Green Fund Management Pte. Ltd., 168 Robinson Road, Capital Tower, #19-15, Singapore 068912

Disclaimer: This presentation has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. This presentation and any references to any capital market products and/or services thereof are for informational purposes only. Nothing shall be construed or deemed an offer or sale of capital market products or services. The target audience for this presentation are accredited, institutional investors or expert/professional investors (as the case may be) only. Any data displayed or referenced are forward-looking in nature and they shall not be regarded as guarantees of actual performance or results. Capital market products and/or services permitted in Singapore may be subjected to selling restrictions imposed by other jurisdictions. You are encouraged to seek independent professional advice should you have any questions.